Exploring Node.js Internals

Aleem IsiakaSince the introduction of Node.js by Ryan Dahl at the European JSConf on 8 November 2009, it has seen wide usage across the tech industry. Companies such as Netflix, Uber, and LinkedIn give credibility to the claim that Node.js can withstand a high amount of traffic and concurrency.

Armed with basic knowledge, beginner and intermediate developers of Node.js struggle with many things: “It’s just a runtime!” “It has event loops!” “Node.js is single-threaded like JavaScript!”

While some of these claims are true, we will dig deeper into the Node.js runtime, understanding how it runs JavaScript, seeing whether it actually is single-threaded, and, finally, better understanding the interconnection between its core dependencies, V8 and libuv.

Prerequisites

- Basic knowledge of JavaScript

- Familiarity with Node.js semantics (

require,fs)

What Is Node.js?

It might be tempting to assume what many people have believed about Node.js, the most common definition of it being that it’s a runtime for the JavaScript language. To consider this, we should understand what led to this conclusion.

Node.js is often described as a combination of C++ and JavaScript. The C++ part consists of bindings running low-level code that make it possible to access hardware connected to the computer. The JavaScript part takes JavaScript as its source code and runs it in a popular interpreter of the language, named the V8 engine.

With this understanding, we could describe Node.js as a unique tool that combines JavaScript and C++ to run programs outside of the browser environment.

But could we actually call it a runtime? To determine that, let’s define what a runtime is.

What is a runtime? https://t.co/eaF4CoWecX

— Christian Nwamba (@codebeast) March 5, 2020

In one of his answers on StackOverflow, DJNA defines a runtime environment as “everything you need to execute a program, but no tools to change it”. According to this definition, we can confidently say that everything that is happening while we run our code (in any language whatsoever) is running in a runtime environment.

Other languages have their own runtime environment. For Java, it is the Java Runtime Environment (JRE). For .NET, it is the Common Language Runtime (CLR). For Erlang, it is BEAM.

Nevertheless, some of these runtimes have other languages that depend on them. For example, Java has Kotlin, a programming language that compiles to code that a JRE can understand. Erlang has Elixir. And we know there are many variants for .NET development, which all run in the CLR, known as the .NET Framework.

Now we understand that a runtime is an environment provided for a program to be able to execute successfully, and we know that V8 and a host of C++ libraries make it possible for a Node.js application to execute. Node.js itself is the actual runtime that binds everything together to make those libraries an entity, and it understands just one language — JavaScript — regardless of what Node.js is built with.

Internal Structure Of Node.js

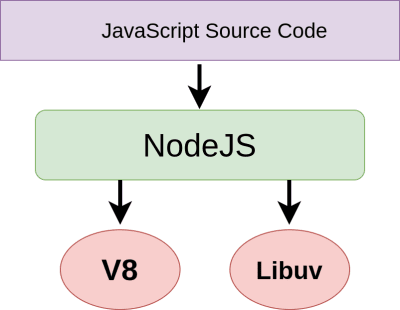

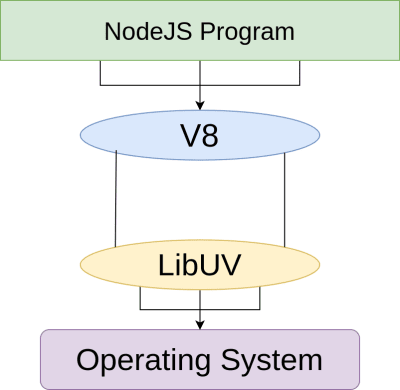

When we attempt to run a Node.js program (such as index.js) from our command line using the command node index.js, we are calling the Node.js runtime. This runtime, as mentioned, consists of two independent dependencies, V8 and libuv.

V8 is a project created and maintained by Google. It takes JavaScript source code and runs it outside of the browser environment. When we run a program through a node command, the source code is passed by the Node.js runtime to V8 for execution.

The libuv library contains C++ code that enables low-level access to the operating system. Functionality such as networking, writing to the file system, and concurrency are not shipped by default in V8, which is the part of Node.js that runs our JavaScript code. With its set of libraries, libuv provides these utilities and more in a Node.js environment.

Node.js is the glue that holds the two libraries together, thereby becoming a unique solution. Throughout the execution of a script, Node.js understands which project to pass control to and when.

Interesting APIs For Server-Side Programs

If we study a little history of JavaScript, we would know that it’s meant to add some functionality and interaction to a page in the browser. And in the browser, we would interact with the elements of the document object model (DOM) that make up the page. For this, a set of APIs exists, referred to collectively as the DOM API.

The DOM exists only in the browser; it is what is parsed to render a page, and it is basically written in the markup language known as HTML. Also, the browser exists in a window, hence the window object, which acts as a root for all of the objects on the page in a JavaScript context. This environment is called the browser environment, and it is a runtime environment for JavaScript.

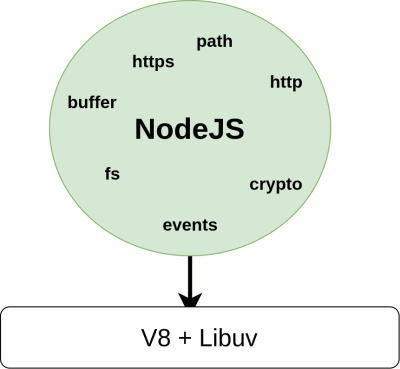

In a Node.js environment, we have nothing like a page, nor a browser — this nullifies our knowledge of the global window object. What we do have is a set of APIs that interact with the operating system to provide additional functionality to a JavaScript program. These APIs for Node.js (fs, path, buffer, events, HTTP, and so on), as we have them, exist only for Node.js, and they are provided by Node.js (itself a runtime) so that we can run programs written for Node.js.

Experiment: How fs.writeFile Creates A New File

If V8 was created to run JavaScript outside of the browser, and if a Node.js environment does not have the same context or environment as a browser, then how would we do something like access the file system or make an HTTP server?

As an example, let’s take a simple Node.js application that writes a file to the file system in the current directory:

const fs = require("fs")

fs.writeFile("./test.txt", "text");

As shown, we are trying to write a new file to the file system. This feature is not available in the JavaScript language; it is available only in a Node.js environment. How does this get executed?

To understand this, let’s take a tour of the Node.js code base.

Heading over to the GitHub repository for Node.js, we see two main folders, src and lib. The lib folder has the JavaScript code that provides the nice set of modules that are included by default with every Node.js installation. The src folder contains the C++ libraries for libuv.

If we look in the src folder and go through the fs.js file, we will see that it is full of impressive JavaScript code. On line 1880, we will notice an exports statement. This statement exports everything we can access by importing the fs module, and we can see that it exports a function named writeFile.

Searching for function writeFile( (where the function is defined) leads us to line 1303, where we see that the function is defined with four parameters:

function writeFile(path, data, options, callback) {

callback = maybeCallback(callback || options);

options = getOptions(options, { encoding: 'utf8', mode: 0o666, flag: 'w' });

const flag = options.flag || 'w';

if (!isArrayBufferView(data)) {

validateStringAfterArrayBufferView(data, 'data');

data = Buffer.from(data, options.encoding || 'utf8');

}

if (isFd(path)) {

const isUserFd = true;

writeAll(path, isUserFd, data, 0, data.byteLength, callback);

return;

}

fs.open(path, flag, options.mode, (openErr, fd) => {

if (openErr) {

callback(openErr);

} else {

const isUserFd = false;

writeAll(fd, isUserFd, data, 0, data.byteLength, callback);

}

});

}

On lines 1315 and 1324, we see that a single function, writeAll, is called after some validation checks. We find this function on line 1278 in the same fs.js file.

function writeAll(fd, isUserFd, buffer, offset, length, callback) {

// write(fd, buffer, offset, length, position, callback)

fs.write(fd, buffer, offset, length, null, (writeErr, written) => {

if (writeErr) {

if (isUserFd) {

callback(writeErr);

} else {

fs.close(fd, function close() {

callback(writeErr);

});

}

} else if (written === length) {

if (isUserFd) {

callback(null);

} else {

fs.close(fd, callback);

}

} else {

offset += written;

length -= written;

writeAll(fd, isUserFd, buffer, offset, length, callback);

}

});

}

It is also interesting to note that this module is attempting to call itself. We see this on line 1280, where it is calling fs.write. Looking for the write function, we will discover a little information.

The write function starts on line 571, and it runs about 42 lines. We see a recurring pattern in this function: the way it calls a function on the binding module, as seen on lines 594 and 612. A function on the binding module is called not only in this function, but in virtually any function that is exported in the fs.js file file. Something must be very special about it.

The binding variable is declared on line 58, at the very top of the file, and a click on that function call reveals some information, with the help of GitHub.

This internalBinding function is found in the module named loaders. The main function of the loaders module is to load all libuv libraries and connect them through the V8 project with Node.js. How it does this is rather magical, but to learn more we can look closely at the writeBuffer function that is called by the fs module.

We should look where this connects with libuv, and where V8 comes in. At the top of the loaders module, some good documentation there states this:

// This file is compiled and run by node.cc before bootstrap/node.js

// was called, therefore the loaders are bootstraped before we start to

// actually bootstrap Node.js. It creates the following objects:

//

// C++ binding loaders:

// - process.binding(): the legacy C++ binding loader, accessible from user land

// because it is an object attached to the global process object.

// These C++ bindings are created using NODE_BUILTIN_MODULE_CONTEXT_AWARE()

// and have their nm_flags set to NM_F_BUILTIN. We do not make any guarantees

// about the stability of these bindings, but still have to take care of

// compatibility issues caused by them from time to time.

// - process._linkedBinding(): intended to be used by embedders to add

// additional C++ bindings in their applications. These C++ bindings

// can be created using NODE_MODULE_CONTEXT_AWARE_CPP() with the flag

// NM_F_LINKED.

// - internalBinding(): the private internal C++ binding loader, inaccessible

// from user land unless through `require('internal/test/binding')`.

// These C++ bindings are created using NODE_MODULE_CONTEXT_AWARE_INTERNAL()

// and have their nm_flags set to NM_F_INTERNAL.

//

// Internal JavaScript module loader:

// - NativeModule: a minimal module system used to load the JavaScript core

// modules found in lib/**/*.js and deps/**/*.js. All core modules are

// compiled into the node binary via node_javascript.cc generated by js2c.py,

// so they can be loaded faster without the cost of I/O. This class makes the

// lib/internal/*, deps/internal/* modules and internalBinding() available by

// default to core modules, and lets the core modules require itself via

// require('internal/bootstrap/loaders') even when this file is not written in

// CommonJS style.

What we learn here is that for every module called from the binding object in the JavaScript section of the Node.js project, there is an equivalent of it in the C++ section, in the src folder.

From our fs tour, we see that the module that does this is located in node_file.cc. Every function that is accessible through the module is defined in the file; for example, we have the writeBuffer on line 2258. The actual definition of that method in the C++ file is on line 1785. Also, the call to the part of libuv that does the actual writing to the file can be found on lines 1809 and 1815, where the libuv function uv_fs_write is called asynchronously.

What Do We Gain From This Understanding?

Just like many other interpreted language runtimes, the runtime of Node.js can be hacked. With greater understanding, we could do things that are impossible with the standard distribution just by looking through the source. We could add libraries to make changes to the way some functions are called. But above all, this understanding is a foundation for further exploration.

Is Node.js Single-Threaded?

Sitting on libuv and V8, Node.js has access to some additional functionalities that a typical JavaScript engine running in the browser does not have.

Any JavaScript that runs in a browser will execute in a single thread. A thread in a program’s execution is just like a black box sitting on top of the CPU in which the program is being executed. In a Node.js context, some code could be executed in as many threads as our machines can carry.

To verify this particular claim, let’s explore a simple code snippet.

const fs = require("fs");

// A little benchmarking

const startTime = Date.now()

fs.writeFile("./test.txt", "test", (err) => {

If (error) {

console.log(err)

}

console.log("1 Done: ", Date.now() — startTime)

});

In the snippet above, we are trying to create a new file on the disk in the current directory. To see how long this could take, we’ve added a little benchmark to monitor the start time of the script, which gives us the duration in milliseconds of the script that is creating the file.

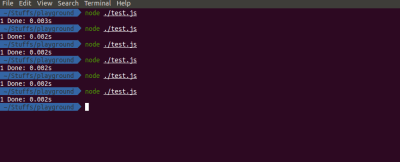

If we run the code above, we will get a result like this:

$ node ./test.js

-> 1 Done: 0.003s

This is very impressive: just 0.003 seconds.

But let’s do something really interesting. First let’s duplicate the code that generates the new file, and update the number in the log statement to reflect their positions:

const fs = require("fs");

// A little benchmarking

const startTime = Date.now()

fs.writeFile("./test1.txt", "test", function (err) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

}

console.log("1 Done: %ss", (Date.now() — startTime) / 1000)

});

fs.writeFile("./test2.txt", "test", function (err) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

}

console.log("2 Done: %ss", (Date.now() — startTime) / 1000)

});

fs.writeFile("./test3.txt", "test", function (err) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

}

console.log("3 Done: %ss", (Date.now() — startTime) / 1000)

});

fs.writeFile("./test4.txt", "test", function (err) {

if (err) {

console.log(err)

}

console.log("4 Done: %ss", (Date.now() — startTime) / 1000)

});

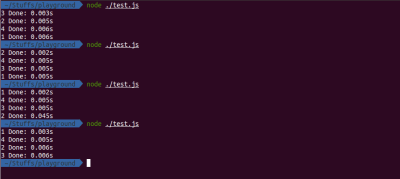

If we attempt to run this code, we will get something that blows our minds. Here is my result:

First, we will notice that the results are not consistent. Secondly, we see that the time has increased. What’s happening?

Low-Level Tasks Get Delegated

Node.js is single-threaded, as we know now. Parts of Node.js are written in JavaScript, and others in C++. Node.js uses the same concepts of the event loop and the call stack that we are familiar with from the browser environment, meaning that the JavaScript parts of Node.js are single-threaded. But the low-level task that requires speaking with an operating system is not single-threaded.

When a call is recognized by Node.js as being intended for libuv, it delegates this task to libuv. In its operation, libuv requires threads for some of its libraries, hence the use of the thread pool in executing Node.js programs when they are needed.

By default, the Node.js thread pool provided by libuv has four threads in it. We could increase or reduce this thread pool by calling process.env.UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE at the top of our script.

// script.js

process.env.UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE = 6;

// …

// …

What Happens With Our File-Making Program

It appears that once we invoke the code to create our file, Node.js hits the libuv part of its code, which dedicates a thread for this task. This section in libuv gets some statistical information about the disk before working on the file.

This statistical checking could take a while to complete; hence, the thread is released for some other tasks until the statistical check is completed. When the check is completed, the libuv section occupies any available thread or waits until a thread becomes available for it.

We have only four calls and four threads, so there are enough threads to go around. The only question is how fast each thread will process its task. We will notice that the first code to make it into the thread pool will return its result first, and it blocks all of the other threads while running its code.

Conclusion

We now understand what Node.js is. We know it’s a runtime. We’ve defined what a runtime is. And we’ve dug deep into what makes up the runtime provided by Node.js.

We have come a long way. And from our little tour of the Node.js repository on GitHub, we can explore any API we might be interested in, following the same process we took here. Node.js is open source, so surely we can dive into the source, can’t we?

Even though we have touched on several of the low levels of what happens in the Node.js runtime, we mustn’t assume that we know it all. The resources below point to some information on which we can build our knowledge:

- Introduction to Node.js

Being an official website, Node.dev explains what Node.js is, as well as its package managers, and lists web frameworks built on top of it. - “JavaScript & Node.js”, The Node Beginner Book

This book by Manuel Kiessling does a fantastic job of explaining Node.js, after warning that JavaScript in the browser is not the same as the one in Node.js, even though both are written in the same language. - Beginning Node.js

This beginner book goes beyond an explanation of the runtime. It teaches about packages and streams and creating a web server with the Express framework. - LibUV

This is the official documentation of the supporting C++ code of the Node.js runtime. - V8

This is the official documentation of the JavaScript engine that makes it possible to write Node.js with JavaScript.

from Tumblr https://ift.tt/2S0e529

No comments:

Post a Comment